A Month in Boston with Ernest Hemingway

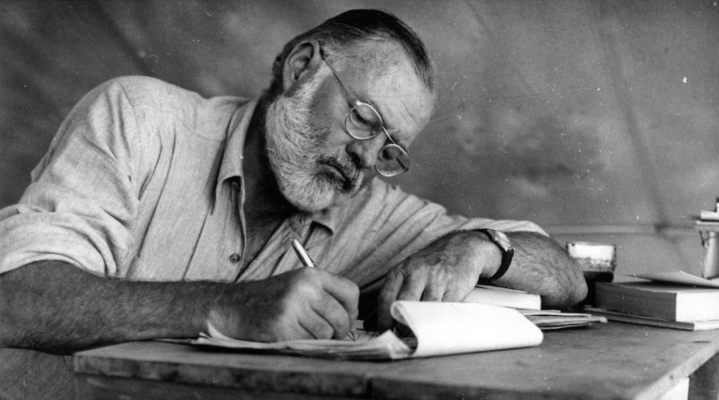

Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) is an important American author of works such as The Sun also Rises, A Farewell to Arms and The Old Man and the Sea. His great achievement in the realm of fiction was to write in a direct, terse and unpretentious prose style. His work is studied in schools and universities throughout the USA and around the world. I have been researching, writing and presenting papers on Hemingway’s achievement at conferences since 2015.

Dr Selma Karayalcin

Every year the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation in Boston, Massachusetts, offers a competitive grant to scholars interested in researching their important Ernest Hemingway Collection, and applications are based on their qualifications but also on their future contribution to Hemingway and related studies. With roughly 90% of Hemingway’s personal papers and letters at the JFK Library, this was a unique opportunity I could not afford to miss. I was lucky enough to be awarded a grant and spent four amazing weeks this summer researching the Hemingway archives at the JFK.

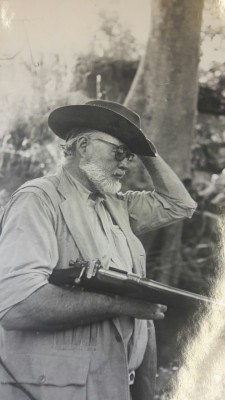

The aim of my research was two-fold: to complete a screenplay, currently in its third draft, about Hemingway’s final years, and to compile an entertaining coffee-table book of ‘Hemingway Aboard’ – Trips to Italy and Africa, and his time in Cuba – with the help of the journals and photographs of his fourth and last wife, Mary Welsh, and adding my own critical commentary.

When Hemingway died, he left behind a number of unfinished works, two of which are integral to my two projects. One is about Africa and is based on his safari in late 1953 and early 1954; it is referred to as ‘The African Book’ (75,000 words). While parts of ‘The African Book’ have been published as True at First Sight (1999), the original manuscript has been heavily edited and the more recent Under Kilimanjaro (2005) is no closer to revealing Hemingway’s intentions. Indeed, the very nature of ‘The African Book’ – as fact, ‘fiction based on fact,’ or fiction – is ambiguous.

The other unfinished work is a novel set in the south of France titled ‘The Garden of Eden.’ I gained a great deal from examining Hemingway’s complete manuscript, as the only available source of ‘The Garden of Eden’ is the 70,000-word novel in 30 chapters published posthumously in 1986 by Scribner’s, whereas the Kennedy Library holds the 200,000-word manuscript in 48 chapters that he had been working on intermittently for almost a decade.

Hemingway had placed these two works in a bank vault for safekeeping and intended to revise and complete them later on. For the general public, these posthumous works are an enjoyable part of the Hemingway canon. For the researcher, however, they are problematic, as they were not yet ready for publication, and clearly any editorial interventions without the author’s approval cannot be true to his intentions. Nonetheless, the works have been altered and abridged, and these changes now affect how readers experience them.

Although I had accessed the online catalogue of the library’s holdings and knew what I wanted to look at, once I arrived at the JFK, the sheer scope of the archives was breath-taking. Hemingway was a hoarder – he discarded nothing: from train tickets and restaurant menus to every draft of his works. And though it was tempting to examine more than I had set out to do, this was impossible because I had to confine my research to accounts of the African safari through his wife’s journal, ‘The African Book’, and those aspects of it that seep into ‘The Garden of Eden.’ Add this to the photographs and numerous letters and personal papers from the period – material unavailable elsewhere – and a tantalising inner story emerges.

Each day I worked on the manuscripts was like entering Hemingway’s personal universe. It was a very emotional experience for me – reading Hemingway’s works written in his own hand or typed by him, with their punctuation errors and spelling mistakes, with passages or words crossed out and corrected, or with the note ‘leave for later’: all this was exciting to read yet sometimes frustrating, as I tried to decipher his handwriting or simply determine what he was trying to say. Ultimately, these are all works in progress.

Some of these works in progress gave me a real sense not only of Hemingway’s writing process but also of his emotional state at the time he was writing. For example, in 1961 he was asked to write a tribute to recently elected president John F. Kennedy. This was during a period when Hemingway found that he was no longer able to write well, which deeply troubled and depressed him. From his manuscript drafts, therefore, we can see that it took him an entire week to write three or four sentences, and when reading them, Hemingway’s anguish and frustration are palpable. He would commit suicide five months later.

The Hemingway Research Grant was an invaluable opportunity for me to examine original documents at the JFK Library. I am energised by the discoveries I have made and look forward to incorporating my findings into my two research projects. In addition, my month with Ernest Hemingway will also have an impact in my classroom. As a teacher of language and literature, I read and analyse poetry and prose on a continuing basis. The beauty of literature is that it has the power to transport the reader to another time and place. At the JFK library, I gleaned countless insights into Hemingway’s personal life and creative process and became more aware of the difficult language choices he made. This experience provided me with new and fascinating perspectives on the writing process itself, perspectives that I can now share with my students in the classroom.